Grenzen des Sichtbaren 2017

Gemeinschaftsausstellung der Gruppe77, ORF GrazAurelia Meinhart hat es bei Piero della Francesca entdeckt. Das im Raum hängende Ei. An einer Goldkette hängt es in einer Jakobsmuschel aus, vielleicht, Marmor direkt über Maria. Sie hat die Hände gefaltet, in ihrem Schoß der schlafende Jesus. Um sie herum vier Engel (wie die Kunstgeschichte weiß) und sechs Heilige. Vor ihr kniet der Auftraggeber des Altarbildes, Federico da Montefeltro. Jener mächtige Condottiere, den Piero in einem nicht minder berühmten Porträt zu einer Ikone der Renaissance macht (ebenfalls im markanten Profil, mit rotem Hut und rotem Wams).

Pieros Ei stammt vermutlich ebenfalls von einem Strauß (das in der Perspektive relativ klein scheint). Interpretationen für seine doch sehr zentrale Präsenz gibt es viele. Das “Weltenei” taucht in vielen Kulturen auf. Für die alten Ägypter symbolisierte das Ei das Leben nach dem Tod, in der indischen Mythologie wird der ganze Kosmos in Form eines Eis erschaffen, Augustinus erklärt es zum Symbol der Hoffnung. Für den mittelalterlichen sächsischen Theologen Hugo von St. Viktor steht es für Christi Tod und Auferstehung. Im konkreten Bild wird es von Kunst- und Kulturhistorikern als Symbol für die Unbefleckte Empfängnis Marias gedeutet.

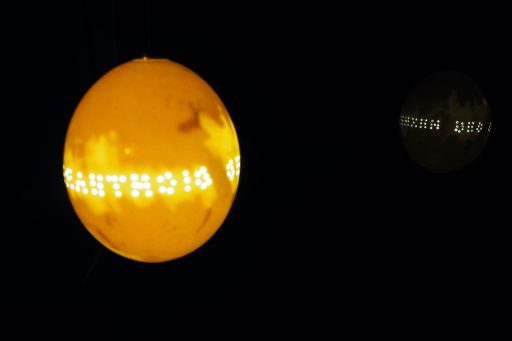

Man kann also sagen: das Ei an sich hat es in sich. In seiner schwer überbietbaren Perfektion eignet es sich speziell als Projektionsfläche. Und genau als solche nutzt es Aurelia Meinhart in ihrer Arbeit. Indem sie vor eine schwarze Plexiglasplatte im schwarzen Alu-Rahmen ein über einen Lichtkanal von innen beleuchtetes Straußenei mit eingefräster Schrift hängt und dieses noch dazu in leichte Rotation gebracht werden kann. Die Schrift auf der Schale ist der Titel von Arbeit und Ausstellung: “Die Grenzen des Sichtbaren”.

Meinhart eröffnet auf elegante Art und Weise ein enormes Assoziationsfeld. Sie erschafft gewissermaßen ihr eigenes “Weltenei”, das einem ganzen Kosmos locker Platz bietet. Wer — Achtung! — in diesen vordringt, kann urknallplötzlich vor dem “schwarzen Loch der Milchstraße” stehen, vor nichts Geringerem als der Unendlichkeit. Die Künstlerin weiß (selbst)ironisch um das Risiko, das die “Verkörperung des Ganzheitlichen” mit sich bringt: “Die Rundung als Unendlichkeit ist fast zum wahnsinnig werden.” Wie würde Piero sagen? “Corraggio!” Nur Mut.

Text: Walter Titz

ORF Graz, Gruppe 77 “Grenzen des Sichtbaren“ 2017

Aurelia Meinhart actually discovered it when she saw Piero della Francesca’s pendent egg. Hanging on a golden thread, it is suspended from a – maybe – marble shell directly above Mary’s head. Surrounded by four angels (as art history will have it) and six saints, she folds her hands, with the sleeping Child on her lap. Before her kneels the man who commissioned the altarpiece, Federico da Montefeltro, a powerful condottiere, who was made an icon of Renaissance by Piero in an equally famous portrait (likewise portrayed in distinctive profile in a red hat and red doublet).

Piero’s egg is probably that of an ostrich, too (although it looks relatively small from a distance). There have been many interpretations of its very central presence. The “world egg” is found in many cultures. For the old Egyptians, it symbolised life after death, and in Indian mythology, the whole cosmos appears in the form of an egg, while Augustine of Hippo declared it a symbol of hope. For Hugo of Saint Victor, a medieval Saxon theologian, the egg stood for Christ’s death and resurrection. In this particular portrayal, it is interpreted by art and culture historians as a symbol of the Immaculate Conception of Mary.

To put it in a nutshell: there is more to the egg than meets the eye. In its almost unsurpassable perfection, it offers an ideal projection surface. And that is exactly how Aurelia Meinhart uses it in her work. Above a light channel in front of a sheet of black Plexiglas in a black aluminium frame she has suspended an internally lit ostrich egg, which can also gently rotate, bearing milled in letters which can be brought into slight rotation as well. The letters on the egg shell spell out the title of her work and of the exhibition: “The Boundaries of the Visible”.

Meinhart elegantly opens an enormous sphere of associations. She has created her own “world egg”, as it were, that provides enough room for the whole cosmos. Whoever – be careful! – penetrates it, could – slap-bang – find themselves facing the “black hole in the milky way”, standing before none other than eternity itself. In her (self) irony, the artist is well aware of the risk accompanying the “embodiment of the holistic”: “To see curvature as eternity almost drives me crazy.” How would Piero put it? “Corraggio!“ Keep cool.

Text: Walter Titz